In the beginning of May, the Indian Premier League (IPL) juggernaut, with more than two-thirds of the fixtures completed, came to an abrupt halt. Stadium lights dimmed. Commentary boxes fell silent. With military tensions mounting between India and Pakistan, the fate of the 18th edition of the franchise-based cricket league hung in the balance.

Then a few days later, just as suddenly, the switch was flipped back on. Players flew out, others flew in. Some teams rose. Others faltered. But the pulse of the IPL? Steady. Loud. Unrelenting. Last week, Royal Challengers Bengaluru (RCB) clinched their first-ever IPL title. With tears in his eyes, Virat Kohli lifted the elusive trophy, in a culmination of years of relentless pursuit, near misses, and unyielding passion. With that, an electrifying season came to an emotional close.

According to Ormax Media’s 2024 sports report, cricket commands 612 million viewers in India. Of these, 86 million are urban IPL franchise loyalists. Google Trends show IPL-related searches topping charts for eight consecutive weeks, barring the brief pause mid-May. In the final week alone, ‘PBKS vs RCB’ clocked over 10 million searches; ‘MI vs GT’ had a search volume of 5 million. This isn’t just consumption, it’s commitment. This is what it means when a game becomes something more than just a game.

Fans cheer before the start of the Indian Premier League final at Narendra Modi Stadium in Ahmedabad, June 3, 2025.

| Photo Credit:

AP

The gulf between domestic cricket and the IPL isn’t as wide as it seems. The skill, the level of competition, even the pressure, it’s all there. What changes is the spotlight. “There’s not much of a difference in the game itself,” says Abhishek Desai of the Gujarat Cricket Association. “It’s all about the exposure — playing alongside the world’s best. And the IPL is louder, flashier, and that makes everything feel bigger.”

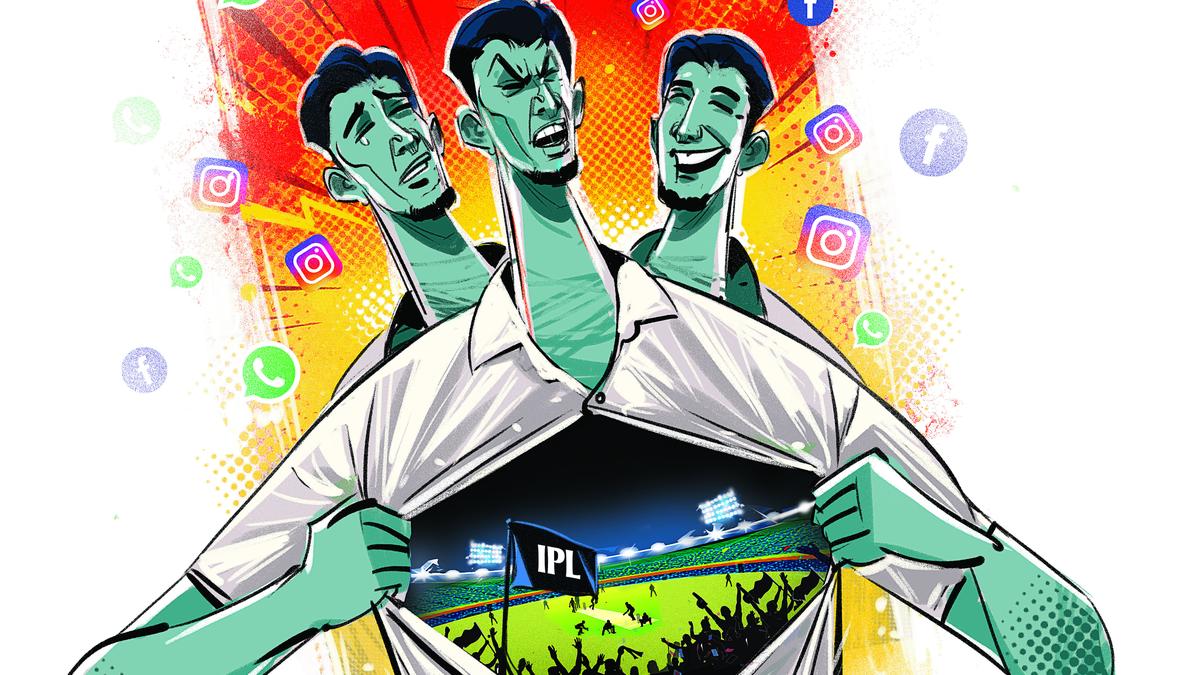

In India, where even silence can be political, the noise around cricket matters. And the IPL, more than any other format of cricket, understands how to dial it up.

Test vs. T20

Tim Wigmore’s Test Cricket: A History offers a sweeping chronicle of a format long seen as cricket’s ultimate test — of skill, temperament, and endurance. But while Wigmore looks back at the grandeur and grit of the red-ball format, the sport has surged ahead. If Test cricket is its pinnacle, then T20, especially in its most commercial, glamorous avatar as the Indian Premier League, has redefined its base.

T20 has reshaped cricket’s priorities, drawing new audiences with its three-hour bursts of action. The IPL, as an extension of this format, has amplified that shift, injecting staggering money, youthful energy, and mass entertainment into the game’s bloodstream. Wigmore portrays Test cricket as both archaic and alluring. He raises a pressing question: can this demanding, five-day format coexist with the electric thrill of T20, especially in its glossy franchise form?

The IPL hasn’t killed Test cricket, it has, in fact, made its survival more urgent. In challenging Test cricket to prove its worth, the IPL has become an unlikely mirror: a rival that paradoxically keeps the older format alive. Today’s aggressive, fast-paced batsmen may light up the IPL, but it’s Test cricket that teaches them the true grammar of the game. The IPL may be where they shine, but Test cricket is where they are forged, say experts.

Sport as story

“The IPL is a McDonaldisation of sport, which is a concept frequently spoken of by sports sociologists,” says Aman Misra, a Ph.D candidate at the University of Tennessee. He studies sports communication and the sociology of sports, particularly public memory and media perception of disability. “It’s tightly packaged, highly produced, and modelled on western templates. To make it work, they have to start creating rivalries, they have to manufacture narratives around wins and losses.”

There is a conscious effort to build parasocial relationships, thinks Misra. “The best way to understand it is that even if the league is ‘constructed’, the emotions it sparks are real. Sports reflects society,” he says.

This emotional mirroring touches fans and players alike. Gujarat Titans’ spinner Sai Kishore understands it. “It’s not bizarre to me. It means the team is theirs, too. They feel the wins, and they feel the losses,” he says.

For comedian Danish Sait, who plays RCB’s irreverent mascot Mr. Nags, defeat feels personal. “You travel with the team, spend time with the players. When they lose, it hurts. But the business side still rolls on, so you keep the performance on. Even my valet tells me, ‘Sir, please come back with the trophy’. I don’t even play! But that’s the magic of sport. It makes you one of them,” he says.

“When I got the opportunity 11 years ago to be the bridge between fans and cricketers, the goal was to humanise the players — to bring them closer. Back then, cricket was all about hero worship, the constant David vs. Goliath narrative. But no one was showing them as real people, just like us, who love the game and have a sense of humour. I really enjoyed speaking the language fans speak and creating something they could connect with.”Danish SaitComedian and RCB mascot

RCB remained among the league’s great enigmas — hugely popular despite never winning the title until this season. The 2024 Ormax report pegs it at 13.3 million fans, just behind five-time winners Chennai Super Kings and Mumbai Indians.

“Everybody loves an underdog,” says screenwriter Navjot Gulati. “RCB’s arc is full of drama, chaos, and heartbreak,” he adds. For years, they came agonisingly close — losing the final in 2009, 2011 and 2016, and pulling off a dramatic comeback in 2024 only to stumble in the playoffs. One of the most consistent teams, RCB made the playoffs five times in the last six seasons.

It’s a cruel irony. A team that boasted T20 swashbucklers such as Chris Gayle and AB de Villiers somehow never managed to translate their talent into silverware. Having won nearly every other cricketing honour, Kohli bore the weight of this one for years. Which is why, Gulati says, “It won’t just be their core fans who’ll celebrate. I think a lot of people will celebrate just because there’s a story there.”

For Mumbai Indians fan Dhruv Shah, co-founder of Funcho Entertainment, a comedy content channel, the appeal lies in sport as an outlet. “Most of us have aggressive, competitive sides, but life gets in the way. The IPL lets us win by proxy. Cricket allows us to win.”

Fandom and identity

‘Sports fandom taps into a deeply human need to belong.’

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The emotion isn’t superficial. It cuts deep. Therapist Meghna Singhal, a Ph.D in clinical psychology, maps fan grief to the DABDA model: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. “Fans genuinely grieve. At first, it’s ‘We didn’t deserve to lose’; then, ‘The umpiring was biased’; followed by ‘If only we bowled that guy’; then comes a week of sadness; and finally, ‘It was still a great season’.”

Cricket is a life marker for actor Nakuul Mehta. His fandom is a dream deferred. “Like most children in India, I once dreamt of playing for the country. But at some point, you realise your ambition outweighs your talent. So you live that dream through your heroes. When they win, you soar. When they lose, it stings, it feels personal.”

He credits the IPL management with building a fandom few saw coming. “When my team loses, it hurts because I lose the right to defend them. But when they win, it feels worth it, like all those years of standing by them finally paid off.”

Singhal adds that team loyalty anchors personal identity. “Sports fandom taps into a deeply human need to belong. When we support a Mumbai or Gujarat, we’re anchoring ourselves to a shared identity,” she says. Psychology calls this the social identity theory, according to Singhal. “Our sense of self is shaped by the group we belong to.”

Meanwhile, veteran sports editor Suresh Menon believes fans are outsourcing emotion. “You look at Kohli and think, ‘Thank God I don’t have to do all that.’ You’ve nominated him to win on your behalf.” He calls it coquette psychology. “Sport is fundamentally meaningless. So we impose meaning, glory, sacrifice, heartbreak. It’s got a story. It’s got memories.”

“When India beat England for the first time — whether at home in 1952 or away in 1971 — it felt like getting our own back on the colonisers. Cricket can mean many things: a way to assert nationhood, to express identity. During the Depression, Don Bradman became a towering figure in Australian cricket, someone the nation could rally around, just like we did with Tendulkar. He didn’t just play for us; he stood in for us. That kind of identification with a sporting hero runs deep. And then there’s the thrill, the unpredictability, the drama, the not knowing how it will end. That’s what pulls fans in, even those who don’t follow every match.”Suresh MenonEditor and columnist

Media arms of franchises are happy to add to the storybuilding. “International cricket doesn’t need to build characters,” Menon notes. “But IPL franchises have private players. So you get social media teams building emotional hooks. Personalities are amped up. Narratives are fed.”

Misra agrees. “Sport has always been likened to war to a certain extent. Journalists love conflicts, rivalries, storylines. We’re not telling Indian audiences what to think, we’re telling them how to think. We are creating meaning through media logic. So even if you’re not playing, you start to carry this conflict emotionally, as though it’s yours.”

That is the aim with which comedian Sait began donning the role of RCB’s mascot. “When I got the opportunity 11 years ago to be the bridge between fans and cricketers, the goal was to humanise the players. Back then, cricket was all about hero worship. I really enjoyed speaking the language fans speak and creating something they could connect with,” he says.

Winning by proxy

For many sporting fans, team loyalty anchors personal identity.

| Photo Credit:

ANI

That effort to humanise players, to bridge the gap between icon and individual, is echoed by players, too. Says Sai Kishore of the Gujarat Titans, “People in Gujarat feel deeply connected to the Titans. Most of us players aren’t even from here. But fans get that local flavour, just like Chennaiites do with Dhoni. That’s love.”

Kishore now calls Ahmedabad his second home. “The connection is real. The IPL is emotionally intense. When we lose, it’s not just about ‘moving on to the next one’. We feel it.”

In the end, only one team gets to lift the trophy. But millions more will feel like they lifted it, too. Because when the IPL rolls into town, the country doesn’t just watch. It plays along, and for a little while, all they are going to be saying is, “Ee Saala Cup Namdu” (this year, the trophy is ours).

The writer is a culture, lifestyle and entertainment journalist.

This article appeared in print in the June 8, 2025 edition of The Hindu-Magazine. It was written earlier and updated on June 4 after Royal Challengers Bengaluru won the IPL trophy the previous evening. The article could not include details of a tragic stampede that took place in Bengaluru on the evening of June 4 during the victory celebration.

Published – June 12, 2025 01:29 pm IST